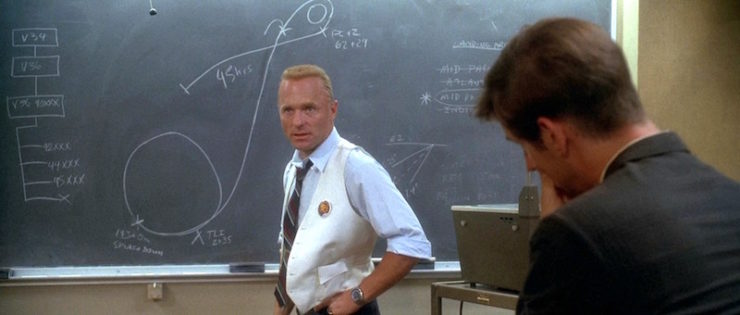

For forty years, media about the space program held to a rigidly binary public image: astronauts were the manliest men who ever manned. They were test pilots, physically tough, able to scoff at pain, laughing in the face of death as they flew into space all in the name of beating the Russkies to the moon. They were backed by close-knit teams of engineers—white men with crewcuts, black plastic glasses, white shirts tucked into black slacks, pocket protectors, and slide rules. Men who barked numbers at each other, along with sentences like “Work the problem, people!” and “We’re not losing an American in space!” and who would, maybe, well up just a little bit when their flyboys finally came back on the comms. They were just as tough and just as manly, but like, nerd-manly.

There was no room in these capsules or HQs for women. The women of the space program were, resolutely, wives. Long-suffering, stoic, perfectly dressed and coiffed, wrangling their children and keeping their homes and posing for Life magazine. They formed their own crew. They met up for sewing circles and fondue parties. They smiled bravely during launches. And, when a man was lost, NASA would call them and send them off to the house of the latest widow, so they could be there before the officials showed up with the news. So she could be there to keep the press at bay, and watch the kids while the latest widow locked herself in the bedroom with a drink and prepared her statement.

Will you be surprised if I tell you that it was never this simple?

I recently read Mary Robinette Kowal’s novel The Calculating Stars, a prequel to her short story “The Lady Astronaut of Mars,” and loved the way she used alternate history to create her her ‘punchcard punk’ universe, looping in and out of the history of the U.S. space program to look at how women and people of color could have been more involved. Kowal’s book was revelatory for me, because here is a version of history where men eventually, finally, listen to women.

Buy the Book

The Calculating Stars

It isn’t perfect—as in our timeline, the women of the Army Air Force’s WASP program are still forced to accept ferrying missions rather than combat, and treated as though their flying is cute. After the war, women are still largely expected to be homemakers whether they want to be or not. But in Kowal’s timeline, a catastrophic event forces humanity to reassess their priorities. Since it seems that Earth will only be livable for about another generation, the remaining humans have to start planning and building space colonies. As Kowal’s main character, Dr. Elma York, repeatedly reminds everyone: if you want a colony, you need women, ’cause men can do as much space exploration as they want, but they still can’t have babies. Thus the Lady Astronaut is born, and soon becomes a media darling as well as a respected member of the alt-historical Space Program, but along the way she has to wrestle with the expectations of a society that wants to keep its gender roles rigidly defined. She has to, in essence, become a myth, a story people tell, before she can become a real astronaut.

Reading the book drove me back through other classics of media that dealt with the space program. I wanted to look at films that revolve around the historical space program to see what these stories could tell us about our recent past, and if they have anything to say about our (hopeful) near-future. The classic pair of films about the U.S. Space Program, The Right Stuff and Apollo 13, both transcend any sort of “based on actual events” narrative to become works of modern mythmaking, but other stories complicate and deconstruct the myth in some fascinating ways.

Establishing the Death Cult in The Right Stuff and Apollo 13

The men of The Right Stuff are arrogant, ornery, and blisteringly competitive. Test pilot Chuck Yeager is literally introduced to the film when he rides in on a gleaming horse, whom he leaves to fondle the gleaming experimental jet he wants to fly. (Yeager was disqualified from the program for not having an engineering degree, but the film implies that he’s also too manly and too independent to submit to the astronaut program.) The astronaut training sequences are set up not as the Mercury 7 proving themselves for space travel, but as tests of strength that turn into competition/bonding exercises for the men. Even the two men portrayed as the biggest heroes – John Glenn and Scott Carpenter – lock eyes during a breathing test, each determined to outlast the other’s strength, rather than simply trying to prove they’re strong enough for the next task.

What’s even more interesting to me is that rather than just stopping at exploring the space program’s he-man aura, the film follows Tom Wolfe’s book by framing the entire project as a sort of national death cult. While the men risk their lives for science, the women, the “Pilots Wives,” are the high priestesses of the cult. The first shot in the film is not Kennedy making a speech about reaching the moon, or engineers mapping out a flight trajectory, or Werner Von Braun deciding to surrender to the Americans rather than the Russians so he can continue his rocketry work—it’s a plane crash. Then we cut to a woman opening her eyes—has the crash been her dream? But then she’s up out of bed and a preacher, clad in black, looking for all the world like the Angel of Death, stalks relentlessly up to her door. Her protest rises from a murmur to a scream: “No, no, no GO AWAY!”

And then we cut to her husband’s funeral.

We never learn her name, or her husband’s. She’s just another test pilot widow, and he’s just another dead flyboy. The next scene holds vigil in the air base’s bar, as the resolutely unglamorous female barkeep adds his photo to the memorial wall. There are a few dozen men up there—all pictured with their planes rather than their wives or children—smiling cockily for the camera.

This is the world we’re entering—not Houston’s control room or a physics classroom, but one where men—and only men—dare death to take them while their wives stay home and wait.

The Right Stuff continues this narrative as the Space Program picks up steam, and each new Mercury 7 hopeful brings along a worried wife. During a cookout attended by the test pilots, the wives huddle in the dark living room, smoking and talking about their stress. Gordon Cooper’s wife, Trudy, is so worried that even though he refers to them as a “team” and claims that he’s only taking dangerous missions to move them up the social ladder, she leaves him and goes back to her parents. The film never mentions the fact that in real life, Trudy was also an avid pilot, and was in fact the only Mercury wife to have her own license. We never see her flying.

When the pilots submit to the grueling training regimen that will winnow them down to the Mercury 7, Cooper begs his wife to come back to create a facade of a stable marriage, and she reluctantly agrees. That reluctance melts away in the office of Henry Luce, publisher of Life magazine, when the astronauts and their wives are told how much money he’s going to give them—if they’re willing to sign their lives over to his publicity machine.

And thus begins phase two. Where the Pilot Wives suffered privately before, now they have to remain stoic and brave no matter what happens to their husbands, while cameras are shoved in their faces. Their reactions to launches are filmed for live broadcast. Journalists root through their garbage. Their lipstick shades are analyzed by the readers of Life. When Gus Grissom’s capsule hatch blows early, and he’s blamed for the loss of the equipment, his wife rages at him in private—he’s just blown her shot at meeting Jackie Kennedy, dammit—but the second the cameras show up she plasters a smile on and talks about how proud she is. Annie Glenn can’t speak in public because of a speech impediment, but she smiles as big as the rest of them. Trudy Cooper is furious at her husband’s continual infidelity, but she’ll stick by him for the sake of the Program.

Later, when John Glenn goes up and is endangered by a potentially wonky heat shield, the press is scandalized by Annie Glenn’s refusal to be interviewed. (They don’t know that she has a speech impediment—and it’s doubtful they would have cared if they did.) The other Wives gather to support her, but can’t do much more than glare at reporters when the cameras aren’t on them. Finally one of the PR wonks has John Glenn call his wife to tell her to play ball with the press. As she cries, helpless, into the phone, we see Glenn expand with anger as he tells her she doesn’t have to talk to anyone. “I will back you up 100% on this. You tell them that astronaut John Glenn told you to say that.” When the PR flack tries to protest, the other astronauts phalanx around Glenn until the smaller, nerdier guy backs down.

On the one hand, it’s sweet, right? Glenn has her back, supports her completely, and becomes even more of a hero by being sensitive to her needs. But at the same time, an utterly infantilized woman has only gained authority by obeying the direct command of her husband. If Glenn had told her to play ball, her own “No” wouldn’t protect her. She has no right to reject her role in the cult. America wants to see her applaud the launch or weep for her husband’s death—either outcome is good TV.

What underlies all of this is the terrifying acceptance of their roles, set against the public’s enthusiasm for all things space. Obviously, the men who okayed the space program knew they were going to lose pilots, the same way the military lost people any time they tested new planes or tanks. You know the risks when you sign up. But the Space Program was different. This wasn’t a bunch of cocksure military men on an air base most Americans had never heard of. This program needed to be successful enough to justify its expense, and before it could become successful, it had to become popular. And it had to remain popular even if some of the astronauts died horrifying deaths, live, on national television. So while the men were paraded around in their shiny space suits and jockeyed to be the most patriotic member of each press conference, their wives were deployed as a fleet of, well, Jackie Kennedys. In good times, held up as style icons and models of ideal American Womanhood. In bad times, expected to present a somber, composed face as the black-suited man from NASA showed up with the news. Required to accept the condolences of a grieving nation, uphold the husband’s memory, and if at all possible, remain in the Texas neighborhood with all the other wives, as an ideal of American Widowhood.

Set over a decade after The Right Stuff, Apollo 13 immediately establishes Tom Hanks’ all-American Jim Lovell as an example of space race-era American masculinity. We meet him as he races across Houston in his red corvette, case of champagne in the back, just barely making it home to his own moon landing watch party, and we’re invited into a world of strict gender-and-generational-norms. The women are bright and glossy in ‘60s dresses and giant hair; the men stride through rooms in shapeless suits waving half-full glasses of whiskey to underline their points. Young astronaut Jack Swigert uses a beer bottle and a cocktail glass to explain a docking procedure to a nubile, giggly young lady. Lovell’s eldest son, a military school student, is allowed to mingle with the adults, but his older sister is left to hover on the stairs and mind the younger siblings. But, Lovell makes a point of admonishing the already crew-cut young man to get a haircut, marking a line between his adult world and his son’s inferior position. This microcosm, with all of its rules and stratification, stands in marked contrast to what we all know is happening in the larger world of 1968.

A few scenes later, when Swigert is added to the crew, he’s given the news while a different nubile young lady awaits him in the shower.

The film reinforces the gender divide continually, in everything from dialogue to the use of color and lighting. Jim and the other astronauts make tough decisions in offices on Earth, or in the cold confines of space. When Fred Haise gets a UTI, he cracks that Swigert must have used his urine hose and given him the clap. They find private corners to look at pictures of their wives, but they don’t discuss their families much, they don’t confide their fears even at the worst moments. They also keep a tight lid on their image as astronauts, cursing like sailors privately, but using family-friendly language when they’re on vox with Houston.

Back on Earth, the engineers use mathematics and logic to solve problems in the fluorescent NASA headquarters. The men don’t show much emotion, crack jokes to break the tension, and work long hours to, as I mentioned above, WORK THE PROBLEM, PEOPLE. In Houston, cigarettes are lit and forcefully stubbed out. coffee is drunk from small Styrofoam cups. Hair is short and aggressively parted. In the capsule, the men spat over hierarchy occasionally, but mostly work together silently to survive.

Meanwhile, the women do emotional work in warmly lit homes, knitting lucky launch day vests, holding crying children, and consulting with religious figures. In these scenes, the effects of the death cult are woven into every moment, as Marilyn Lovell and Mary Haise perform their public duties as astronaut wives, while waiting to see if it’s their turn to become icons of widowhood. Mary Haise is younger than Marilyn Lovell, already has two small children, and is enormously pregnant at the time of the launch—a reminder of her role as long-suffering mother. Marilyn’s relationship to the world is shot through with magical thinking—she frets that the mission is the unlucky #13, she panics when the she loses her wedding ring the night before the launch, she has nightmares of Jim dying in space that recall the dreams of astronaut’s wives in The Right Stuff. After the accident she does her best to ignore the reporters. She does her crying in private, and sits stoically beside the family priest during the long moments when the Apollo 13 capsule bobs in the water, live on TV, before the men have opened the hatch and proved they’re alive.

The film creates an interesting thread in with the Lovell children. Only the eldest son, James, was allowed to attend the party in the opening scene; his sisters and brother only joined for the moon landing broadcast itself, the three of them sit on the floor in front of the TV like children do while James stands beside his father. After the accident, he watches the Apollo 13 landing on TV in his classroom at St. John’s Northwestern Military Academy, surrounded by classmates. At one point his teacher walks by and squeezes his shoulder in support, but he isn’t given privacy, an empty room to watch, nothing. If his father is dead, he’ll learn it in the same moment his friends do.

Back at home, the youngest son is left out of most of the public worry, but both of the daughters already have roles to play. Before the accident, Marilyn forces the older daughter, Barbara, to get dressed and come to Houston HQ to watch her father’s TV broadcast rather than allowing her to stay home and mourn the break-up of the Beatles. After the accident, the daughters come with Marilyn when she visits Jim’s mother in her nursing home. While the press films Marilyn watching the capsule landing, she keeps her elder daughter hugged tight to her side, while her younger children, in a horrifying mirror of that opening scene, sits on the floor at her feet. Neither daughter is able to mask their fear.

These scenes (which I find to be the most brutal in the film) underline the idea that the kids are being inducted into a particularly weird ritual. Rather than just being able to celebrate or mourn their father, they’re expected to perform their worry and relief for an audience—essentially they’re performing patriotism. Whatever their personal beliefs, being put on display in moments that should be private creates a counterpoint to the image of “rebellious youth” of the late ’60s and early ’70s.

The film makes a point of commenting on America’s boredom with the Space Program: during the pre-accident broadcast, one of the NASA reps tells Marilyn that they’ve been dropped by the networks. Houston hasn’t told the boys that they were bumped, so they joke around, demonstrate some of the effects of zero gravity, and Swigert confesses that he hasn’t turned his tax return in yet. For a few moments the Marilyn sits with Mary Haise and her children, her own kids seated in front of her, and they all watch the astronauts antics together, the only audience, playing their roles for no one. Bachelor Swigert, nervously babbling about his taxes, has no one there to watch him. After the accident, though, Apollo 13 is on every channel. The America of 1970 has no interest in watching the clockwork performance of American Hero and American Family, but they’ll tune back in for the death cult.

A Brief Note on the Erasure of the Mercury 13

Both The Right Stuff and Apollo 13 portray a gulf between men and women in the space program. There are astronauts/engineers, and there are wives/widows. The Netflix documentary Mercury 13 shows us that there was, briefly, a third path. It follows a group of women who participated in astronaut testing, and were found to be more than qualified to go into space alongside the men, but were denied a shot because the space program was so dedicated to the heroic male myth it had begun to create for itself. This gender divide was certainly not set in stone: cosmonaut Valentina Tereshkova took a triumphant spaceflight in 1963, the product of a Soviet program that was more interested in trying to prove Russian superiority than in building a mythology around he-men and nurturing women. The documentary also briefly highlights Eileen Collins, who became the first woman to pilot a shuttle in in 1995, when she piloted STS-63, the first rendezvous between Discovery and the space station Mir. The Mercury 13 were idols to Collins, inspiring her to become a pilot and to work her way through astronaut training, and when NASA asked her for her invitation list for the launch, she listed all thirteen. The organizers, to their credit, insisted that they weren’t going on Collins’ list after all but would be invited as honored guests NASA itself. The documentary ends with a scene of the surviving members of the 13 watching a woman pilot a shuttle into space.

None of the 13 are mythologized in the way that the Mercury 7 and later male astronauts were. Their stories are presented as short, fact-filled anecdotes. There’s no footage of them joking around together, or appearing on panels trying to one-up each other. Their husbands never walked a runway or giggled about meeting Jackie Kennedy. They were competent pilots, war veterans, wives, and mothers. A few of them worked with feminist organizations later on in their lives, and a few of them became test pilots, though they never got to fly anything as revolutionarily fast as the Chuck Yeagers of the world. Their stories resolve with them finding closure by witnessing a later woman’s triumph.

One would think that by turning to fiction we could finally see women being heroic astronauts, but even here, most stick to a very constrained script. How to fit women into the space program? Emphasize their roles as wives and mothers. Make sure they talk about love and pride rather than records or speed. To see how the tension between woman as astronaut and woman as wife/mother/icon of womanhood are still playing out in our mythologizing of the space program, brief looks at Gravity, Interstellar, and Hidden Figures are in order before we can see how Kowal resolves these issues in The Calculating Stars.

The Astronaut as Mother in Gravity

Gravity is set in the near future, assigning its mission a number that’s still a bit beyond what NASA’s reached. The mission itself is an odd hybrid: first-time astronaut Dr. Ryan Stone is installing a piece of medical equipment on the Hubble that will help it scan further into space, and veteran astronaut Lt. Matt Kowalski seems to be testing a jetpack. Especially given that this is meant to be in the future, Kowalski is a weird throwback. He’s military, he blasts Hank Williams Jr. over the comms, tells wild tales of wives running off with other men, and references owning both a GTO and a Corvette.

He’s basically an Apollo astronaut.

Except, again, astronauts aren’t really like this any more (if they ever were) and this is supposed to be in our future. He’s far too young to have been one of that early ’60s crop of he-men. Meanwhile, Sandra Bullock’s Ryan Stone is a god-awful astronaut. She’s still space-sick, despite presumably being up there for a weeks by the time we meet her. She drops everything she picks up, is openly uncomfortable, ignores orders from the mission commander, and later admits to crashing NASA’s flight simulator every. single. time. she practiced a landing. The Voice of Houston (Ed Harris! Mr. Space Himself!) repeatedly tells Kowalski it’s been an honor working with him. Dr. Sharriff (the other non-career astronaut specialist on the mission) dances around on the end of his tether like a happy child, and the other crew in Explorer station sound fine. Only Stone is a sick, scattered mess. Kowalski finally asks Houston for permission to assist her, and he flirts with her while he helps her turn bolts.

He’s joking, easy, as casual as Han Solo…until debris comes flying into their orbit, and he goes full career military, barking orders and rescuing a panicking Stone. When we get into Stone’s backstory, we learn that her fist name is Ryan because her parents wanted a boy. She had a daughter who died, seemingly fairly recently, and her grief has destroyed her. She lives her life as a cycle of obsessive work, followed by mindless driving at night until she’s exhausted enough to sleep. No partner is mentioned, no friends, she has no personality or interests at all. While Kowalski has clearly lived a life, Stone has been a mother, and is now a mourner. The film implies that her journey into space is simply a continuation of her driving sessions: she wanted to go far enough to escape her grief.

Not once, but three separate times the film allows Kowalski to be a hero at Stone’s expense. First he rescues her when she spins away into space. Then he chooses to sacrifice himself for her when it becomes clear they can’t both make it to the Soyuz capsule. He orders her to repeat “I’m gonna make it!” as he floats away to his death. As soon as a shell-shocked Stone makes it inside the capsule—repeating “I had you, I had you” like a mantra, referring directly to Kowalski but also recalling her failure to save her child—director Alfonso Cuarón underlines the motherhood motif in this shot:

Stone has to essentially give birth to herself in order to return to earth, and life. A few scenes later, however, Stone gives up yet again. She realizes the Soyuz is out of gas, curses, cries, and quits. She makes no effort to MacGyver her way out of the situation, as the Apollo 13 astronauts did. She doesn’t fall back on other knowledge or training, the way Gordon Cooper did when some of his capsule’s systems failed during 1963’s Faith 7 flight. She calls out to Houston intermittently, asking for outside help or instruction that does not come. Finally, she makes contact with a man on a HAM radio, but hearing him sing a lullaby to his child she breaks down completely. She murmurs that she used to sing to her baby, and turns her oxygen down, resolving to let a random man sing her to sleep, too.

This is a fascinating choice. We already know she’s a grieving mother. Just the ongoing stress and despair of her situation could have lead to her giving up, right? But instead the film gives us a scene that pummels us with her sorrow, and reminds her, and the audience, that her daughter isn’t waiting for her back on Earth. Her decision to die is rooted in her motherhood, just as her decision to come to space seems to be rooted in grief.

But then!

Kowlaski returns, opens the hatch door, and comes in full of quips about his space walk and inside intel on the Russian astronauts’ vodka supplies. Stone is, understandably, shocked. Kowalski explains how she can use the capsule’s landing jets to get the Soyuz over to the Chinese station and then use the Chinese capsule to get back to Earth. It won’t matter that she can’t land, cause she just needs to survive the crash. Then he asks her, “Do you want to go back? Or do you want to stay here? I get it—it’s nice up here. There’s nobody here who can hurt you.” But she could also try to recommit to life and “sit back enjoy the ride.” She wakes to alarms blaring, and immediately shakes herself and does exactly what Ghost Kowalski told her to do.

Now the movie is giving us two choices here, and I don’t particularly like either of them. If Kowalski’s a vision, that means a man had to literally come back from the dead to rescue Dr. Ryan Stone; if Kowalski’s a hallucination, Dr. Ryan Stone’s brain already had the information she needed to survive, but had to frame it as being handed down by a man in order for her to accept it. The female astronaut, trained doctor, grieving mother, has to follow the lead of swaggering male Apollo-throwback in order to survive space and get back to Earth. She accepts this so completely that as she fires up the landing jets, she talks to Kowalski, first thanking him, and then describing her daughter and asking him to look after her in the afterlife. On the one hand, she’s letting both of them go so she can truly live again. But she’s also turning the care of her daughter over to this man she’s only known for a few months, rather than to any other beloved dead. As she begins re-entry, she tells Houston, “It’s been a hell of a ride.” Knowing that this may be her last message, she chooses to riff on Kowalski’s words to her, rather than sign off with thoughts of her own.

The thing that startles me here isn’t just that the female astronaut’s autonomy and competence is undercut at every turn: it’s that the film also finds ways to reinforce the idea that a woman’s role is to shepherd the death cult. Stone is a mother in mourning, a sufficiently feminine archetype that her career is acceptable. But now that Kowalski has sacrificed himself for her, she also goes into the last section of the film carrying his memory. Assuming she lives after she makes it back down, she’s obviously going to tell NASA all about his heroic exploits; her own actions in space were entirely framed by his help (even after he died), and rather than going home under her own power, she goes back to Earth bearing the last chapter of his myth.

Daughters and the Death Cult in Interstellar

The following year, Interstellar played with the same gender binary. Why does Matthew McConaughey’s adventurous, laconic former astronaut go into space? Because life on Earth is failing, and a secret, last-ditch space program recruits him to find humanity a new home, thus saving the species. He does this even though it will mean sacrificing his life with his beloved daughter Murph and his, um, less beloved son, Tom. (Bet you didn’t remember Tom, did you? Don’t worry, I don’t think Coop remembers him, either.) Cooper’s mission is intrinsically heroic, and removes him from doing the day-to-day work of raising a family.

Why does Anne Hathaway’s Dr. Amelia Brand go into space? Because her dad, Dr. John Brand, is the guy running the program, and she was born in it, molded by it. Why does Cooper suggest a particular order of planetary visits? Because he’s making an absolutely rational choice to go join Dr. Mann, who is still broadcasting and thus, presumably, alive.

Why does Dr. Brand suggest going to a third planet, despite the lack of a broadcast? Because her lover, Edmunds went on ahead of them, and she wants to join him. She even offers a pseudo-scientific explanation for her plan, saying, “love is the one thing that we are capable of perceiving that transcends dimensions of time and space”, and suggesting that there has to be a reason that humans are guided by love. Cooper, who was not raised in the program, but only recruited at the very end, overrules her, insisting they go on to Mann’s planet, which turns out to be as uninhabitable as Mann is space-crazy.

When we cut back to Earth, why has Murph spent her entire life studying mathematics and physics? Because she’s volcanically angry with her father for abandoning her, so she works on a way to save humanity that doesn’t involve the giant death-defying trip he’s undertaken.

Meanwhile, Dr. Brand has arrived at the last, habitable planet, and we see her burying Edmund’s remains, alone, sobbing. Her intuition was correct, and if Cooper had listened, they would have found a healthy planet, and he might have been able to see his daughter sooner. After Cooper makes it back to Earth his now-elderly daughter tells him to go back to Dr. Brand so she won’t be alone, so the man who kinda sorta ruined Brand’s life steals a ship and heads out to rejoin a woman who has no reason to like him.

The men’s decisions are logical, cold, calculated: if humanity is to survive, sacrifices have to be made, space colonies have to be established, families have to be abandoned, lovers have to be given up. The women’s choices are emotional, fueled by rage and/or love. Amelia Brand travels to space to continue her father’s work, and makes decisions in the belief that she’s being guided by “love”—again a trained scientist is falling back on magical thinking. Murph Cooper dedicates her life’s work to rebelling against her dad’s life’s work, so her own scientific study is completely bounded within her grief for her father. And in a neat metaphorical trick, Interstellar underlines the same pairing of motherhood and mourning that Gravity was obsessed with: Murph’s salvation of humanity could be seen as a titanic act of mothering, while Dr. Brand is off becoming the new Eve to a previously uninhabited planet. Both women are defined by loss, and even though they’re scientists in their own right, they enact the grief-stricken roles that are expected of them as women in a space program.

Mothering and Math in Hidden Figures

Hidden Figures takes on a couple of tasks simultaneously: educating (all) people about a piece of history that’s been erased; showing (white) people what life was like under Jim Crow laws; and underlining the femininity of its protagonists by focusing on their domestic lives as much as their careers. Watch The Right Stuff or even Apollo 13, and you won’t see too many Black faces. You won’t see Katherine Johnson, even though she was the one who worked out the numbers for Glenn’s flight, and was sometimes in the control room. You won’t see Mary Jackson, who worked on the Mercury rocket, or Dorothy Vaughan, who was making the IBMs work downstairs, or even any of the white female computers. The film adaptation of Hidden Figures therefore has to do the work of reinserting them into story they never should have been edited from. But, since seemingly any woman involved in the space program has to fit at least slightly into this binary mythology, the film also has to remind the audience that these are daughters, mothers and wives.

It has to give us scenes of them feeding their children, tucking them in at night, taking them to church or to the library. It shows us the widowed Katherine Johnson falling in love with the man who becomes her second husband. It shows us Mary Jackson flirting with John Glenn to the horror of her friends. Where The Right Stuff showed us white male astronauts assessing groupies at a Florida tiki bar, and Apollo 13 made time for Jack Swigert’s shower scene, Hidden Figures ticks off the “women express love and solidarity while laughing and dancing together in a kitchen” box.

Where the male astronauts’ family lives were framed in terms of them explaining their missions to their kids, or comforting their terrified wives, the women of Hidden Figures spend time educating their children and making their meals. Where the astronauts’ wives are feted by the public, and put on the cover of Life, the women of NASA have long hours and rigid dress requirements. After Soviet cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin becomes the first man in space, Al Harrison (a pastiche of several real department directors) gives a speech warning his people that they’re going to need to work even longer hours until the Mercury mission is accomplished. He barks at them to call their wives and explain:

Late nights are going to be a fact of life. Don’t expect your paychecks to reflect the extra hours it’s going to take to catch and pass those bastards—for anyone who can’t work that way, I understand. For the rest of you men I suggest you call your wives and tell them how it’s going to be.

The men dutifully do so, but, as usual, his own assistant (a white woman) and Katherine have been left out of the speech. Toward the end of the scene, one of the white male mathematicians passes the phone over to Katherine. It’s an oddly touching moment. After all of her struggles she’s been accepted as just one of the guys—of course she’ll be working late with them, and she’ll need to call home, too. It’s also infuriating for the audience though, because we’ve already watched her work late throughout the film. We know that she’s the one who also puts dinner on the table at home. As she explained to her daughters when she took the job, she has to be Mommy and Daddy, and doesn’t have a wife to call.

A Historically-Accurate Way Forward in The Calculating Stars

What do we want the American space program to look like? If this is going to be one of our central national mythologies, shouldn’t we celebrate the version that includes everyone’s work? Why do the films about our space travel insist on adhering to an idea of a natural order? It made a certain amount of sense for The Right Stuff and Apollo 13 to uphold the gender divides and death cult rituals, because both of those films were dramatizing real, historical events that their audiences had also lived through. But why did Gravity and Interstellar go to such lengths to portray their female astronauts as emotional wrecks? Why did Hidden Figures feel the need to reassure us that these accomplished women were also loving wives and mothers? Why do all the films seem to feel that they have to achieve some sort of weird balance between masculine math and science and feminine love and intuition? Having watched all of these movies, I went into The Calculating Stars excited to see if Kowal felt the same need to create this balance, and was pleased that she allowed her story to take a somewhat different path.

In her effort to break ground while also honoring the history of this timeline, Kowal spends much of The Calculating Stars emphasizing the gender dynamics of the time, and then finding ways to wiggle around them. It’s an ingenious way to explore gender dynamics. Kowal embraces the idea that biology is destiny in order to force her male characters’ hands: to save the species and eventually establish space colonies, they need to employ a fleet of qualified women—would-be mothers—in the nascent space program.

In Elma York, Kowal gives us the perfect protagonist for a weird, sideways-Mad Men era. She’s a brilliant mathematician. She’s married to an engineer who respects her intellect. She has debilitating anxiety because of emotional abuse she suffered during college. As a WASP she was a great pilot, but wasn’t able to rise through the ranks like her male colleagues. She becomes a high-ranking computer with the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics, (which transforms into the International Aeronautics Coalition as the world works together to find a way off the planet), but as a woman she can still be rebuked or ignored by men who aren’t her equal. She becomes “The Lady Astronaut” by accident, when she appears on the “Ask Mr. Wizard” kids’ show to explain the math behind flight trajectories to children, and he gives her the nickname. Since she’s using an acceptable female role (teacher of young children, not threatening PhD) she’s allowed to keep the moniker as a way to bring more human interest to the space program. From there, she’s able to gradually chip away at the gender roles that her male colleagues have never questioned, until she and a few other women are allowed to apply for astronaut status.

Buy the Book

The Fated Sky

But Kowal also draws on the history of Hidden Figures and We Could Not Fail, by showing the tensions between even the progressive-minded white survivors and the post-disaster Black community. When Elma and her husband flee to Kansas City, she’s taken in by a Black couple, a World War II vet named Eugene, and his wife, Myrtle. Rather than making Elma York a perfect stand-in for today’s values, Kowal reckons with the reality of 1950s America. Elma means well. She’s Jewish, experiences prejudice, and has lost people to the Holocaust. But she’s also never had a close Black friend. And to be fair, Myrtle repeatedly offers her pork and bacon and never remembers that Saturday is Elma’s Sabbath. But as refugees pour in, Elma simply doesn’t notice that all of the people staggering into resettlement camps are white. It isn’t until Myrtle points it out to her that she offers to help with a rescue effort aimed at Black neighborhoods. It isn’t until Eugene tells her about the Black flying club that she thinks to enlist Black female pilots to join her white friends as they make a big push toward getting women included in the Space Program. But once Elma has been nudged, she owns up to her mistake, and makes an effort to include all the women who are interested in flight. By reckoning with historically-accurate prejudices, Kowal is able to honor the work of women and people of color, while also giving us flawed heroes who actually learn and grow on the page, rather than giving in to white savior tropes.

And in one of my favorite moments in the book, Kowal even gives a nod to the death cult. As Elma walks toward the shuttle for her first mission, she finally understands why NACA gives the astronauts’ families a prime viewing platform for each launch: by putting them up on the roof of Mission Control, they keep them out of reach of the press. If her shuttle explodes, her bosses will surround her family and make sure that no embarrassing moments of grief make into the papers, and thus the program can go on with carefully vetted statements of mourning. It’s a small moment, but an excellent way to hook her heroine’s story into the classic binary of male adventure and female grief.

Most importantly Kowal finds a way to re-tell this mythology story so it honors all of the people who got us into space.

Leah Schnelbach still doesn’t want to go into space, but she’s glad some of these people did. Come join her in the infinite abyss of Twitter!